Chronology

People lived in Meganisi since the Neolithic Period (7000 – 3500 BC). From that time, a stone tool was found, which is part of the Dierpfeld Collection, which adorns the Archaeological Museum of Lefkada (Wilhelm Dörpfeld, 1853-1940, was a German architect, best known for his contributions to classical archaeology. Contributed to the excavations of ancient Olympia, as well as the discovery of Troy alongside Henry Schliemann). From the late 1880s and for many years afterwards Derpfeld excavated various parts of Lefkada and passionately supported the theory that Homeric Ithaca is the present day island of Lefkada.

The first name of Meganisiou was Tafos, later it was also called Tafiousa. He received it from its settler and first king, Taphius. Taphius and his brother Teleboas were the sons of Hippothea, by Poseidon, daughter of the Lefkadian Lelegas. According to others, of Mystor, the son of Perseus.

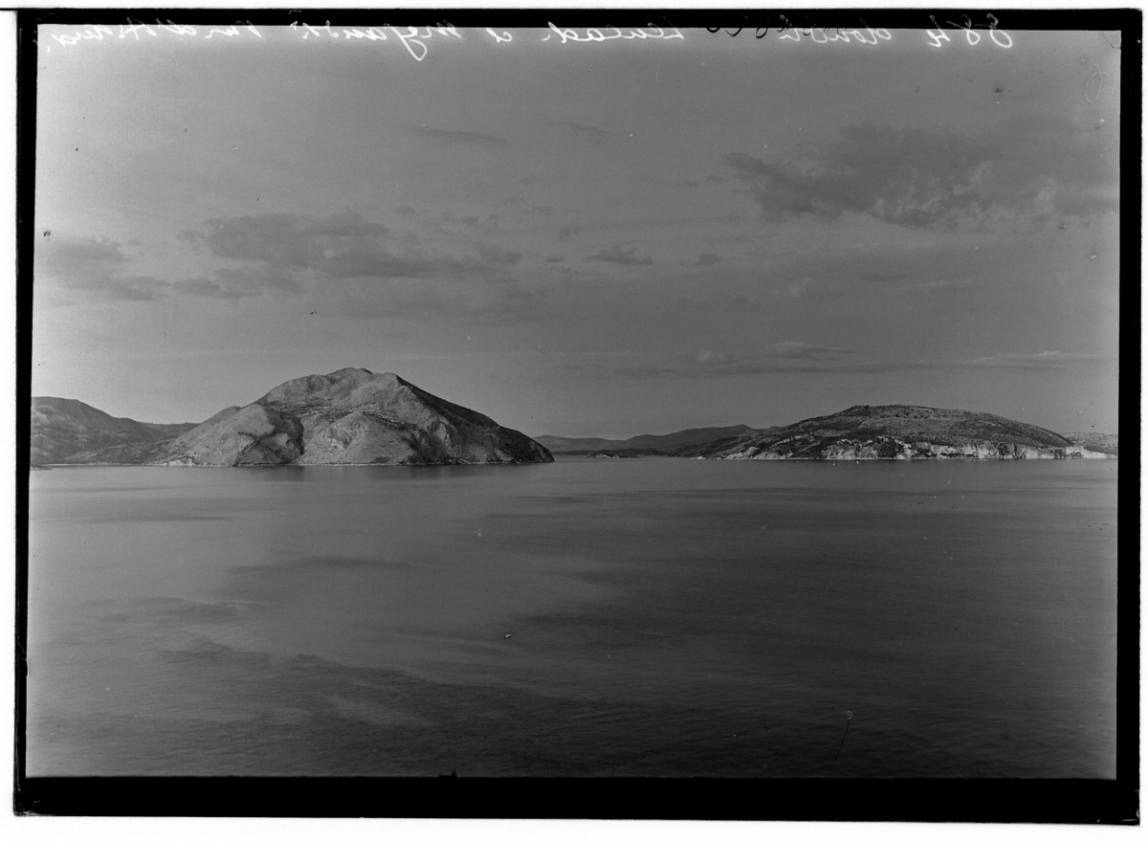

All the islands east of Lefkada and west of Sterea: Skorpios, Sparti, Meganissi, Kalamos, Kastos, etc., were called Tafios or Teleboides islands. And the sea between them Televoia or Tafia.

The Taphii also ruled Acarnania before the Kefallinians came. Tafios was succeeded on the throne by his son Pterelaos. His grandfather, the sea god Poseidon, gave him a golden hair on his head that made him invincible and immortal. In order to assert claims of their grandfather Mystoros, the children of Pterelaos, seized the oxen of the king of Argos, Electryon. In the fight that took place, all eight sons of Electryonos lost their lives. He, in order to avenge their death, gave his daughter Alcmene to the brave Amphitryon (Heracles’ father) and asked him to punish the Taphians. Amphitryon from Thebes gathered a large army and after reaching the islands of Taphia he besieged them, conquered them and gave them to Elios and Cephalus, the grandfather of Laertes. In commemoration of his victory, Amphitryon offered tripods to Ismenius Apollo. Herodotus writes that he saw him and even had the inscription: “Amphitryon raised me from Teleboaon”. There was also a statue of him as the winner of the Tombs.

Homer mentions that Aghialos, a wise man and a close friend of Odysseus (Odyss. a 270) and then the son of Mentis, in whose form Athena presented herself to Telemachus and gave him courage, reigned among the Taphians. At one point in his speech he says: “Mentis Aghialoios daifronos ichomai is a son, atar Tafioisi filiretmoisin anasso.” That is: “I boast that I am Mentis, the son of the wise Aghialos, and I am king among the sailors of the Taphians” (Odyss. a 180-181 c).

He then mentions that he is going to Temesis to give iron and take copper. The Temesi was in Italy, but many identify it with the Tamassos of Cyprus, which was famous for its copper mines. However, the Taphios may also be referred to as pirates (Odyss. x 461, o 427, o 428), a common thing at the time (Odyss. o 450), but it seems that they were excellent merchants, since only they traded in iron, and worthy and brave sailors, because while many Greeks believed in the myths which the Phoenicians spread about Scylles, Charybdis, etc., and did not dare to open again to the sea, they furrowed the whole Mediterranean and competed with, defied and challenged (Odyss. o 427) even these famous Phoenicians.

The Latin writers maintain that Capria (Capri) was a colony of the Tafii.

The biography “About Homer Genesis and Biotis” attributed to Herodotus is disputed by many and they call the author pseudo-Herodotus. It mentions that Homer met a certain Mentis in Smyrna. Based on it, Ragavis writes: “Unless Mentis a famous Lefkadian merchant and shipowner received Homer from Smyrna and toured him to those places the poet knew”. Even if this work is not by Herodotus, but by a grammarian of the 2nd BC. century, as is supported by many, and again informs us that more than a thousand years later they believed that there was a worthy sailor and merchant in Lefkada who could guide Homer to these mythical places. And this Mentis, could only have been from Tafo, the birthplace of the Lefkadian sea wolves.

The huge boulders that are still visible in the port of Vathi show the maritime culture of the island during the Mycenaean period.

The Taphii could not be absent from the Trojan War. They participated with forty manned ships, a formidable number when you consider that Aedes or Odysseus sent only twelve each. Euripides underlines the fact in Iphigenia or in Aulidis:

“The warlike white oars

of the Tombs, the king the Great

ruled, of Phyleas the child,

who left the islands, the Echinades,

where sailors can’t yoke”.

The German archaeologist Wilhelm Dierpfeld in his theory of Homeric Ithaca mentions Lefkada as Ithaca, Kalamos as Tomb and Meganisi as Krokylia. Kalamos is one of the islands of the Tombs and certainly its inhabitants would play an important role in their naval races. But it does not have such harbors as could protect their numerous ships, nor would the infamous Tafian sailors ever surrender their ships to be wrecked in the wild waves of the almost plagued Kalamos.

Then, Meganisi follows the historical fluctuations of Lefkada.

Especially after the Corinthians came in the 7th century BC, when it becomes its colony and ally, its naval and military power follows the Corinthians in hostilities. Indeed, Lefkada participates in the Persian Wars by sending three ships to Salamis and an army to Plataea. During the Peloponnesian War, it was fatally on the side of the Corinthians and thus of their allies the Spartans, who needed experienced naval forces.

In the Hellenistic era, Lefkada joined the “Council of Akarnans” and became its capital (272-168 BC). Apparently, this confederation also includes Tafos. After 168 BC and the arrival of the Romans, the area declines and declines. However, it is considered a transit station, as can be seen from the passage of Apollonius of Tyanaes on his return from Rome. Plinios the Elder calls Meganisi Tafiousa. He claims that there are miraculous stones in it (see “Pharmakopetra”, D. E. Soldatou, “Lefkaditika short stories”, fagotto, 2017, p.: 111).

During the Byzantine era, the entire region was administratively under the Despotate of Epirus. Since then, Lefkada has changed many owners, since it passed through the hands of the Orsini (counts of Kefalonia), the Angeavian dynasty of Naples (who were also the ones who gave it the name Santa Mavra, after their French patron saint), Walter Bryennius , Gratianos Georges and Tokkos. At the time of George the Venetian, in 1357, the revolt of the peasants broke out, also known as the “revolution of the boukendra”, which five centuries later would inspire Aristotle Valaoritis to write “Foteinos”.The Florentine priest K. Buondelmonti he mentions in his travel descriptions in the middle of the 16th century: “Finally, to the east [of Lefkada] some uncultivated islands appear, which were once inhabited by Brothers [kalogeri?], but which as a result of pirate attacks have now been deserted”.

So in a period that was predominantly feudal, Meganisi kept a few inhabitants, and those not permanently. Cultivable lands are limited and usually belong to owners from Katochori, Poros or Fternos. Let’s not forget that the lack of political stability leaves room for waves of pirate raids, making unprotected Meganisi an easy target for plunder. The popular chant: “Tourlos laon elglitose / and again it will escape”, which has survived the ravages of time, as well as some toponyms, testify that there were even rudimentary fortifications, especially on the top of Tourlos (a corruption of Troulos), where a stone low wall, apparently for defensive reasons.

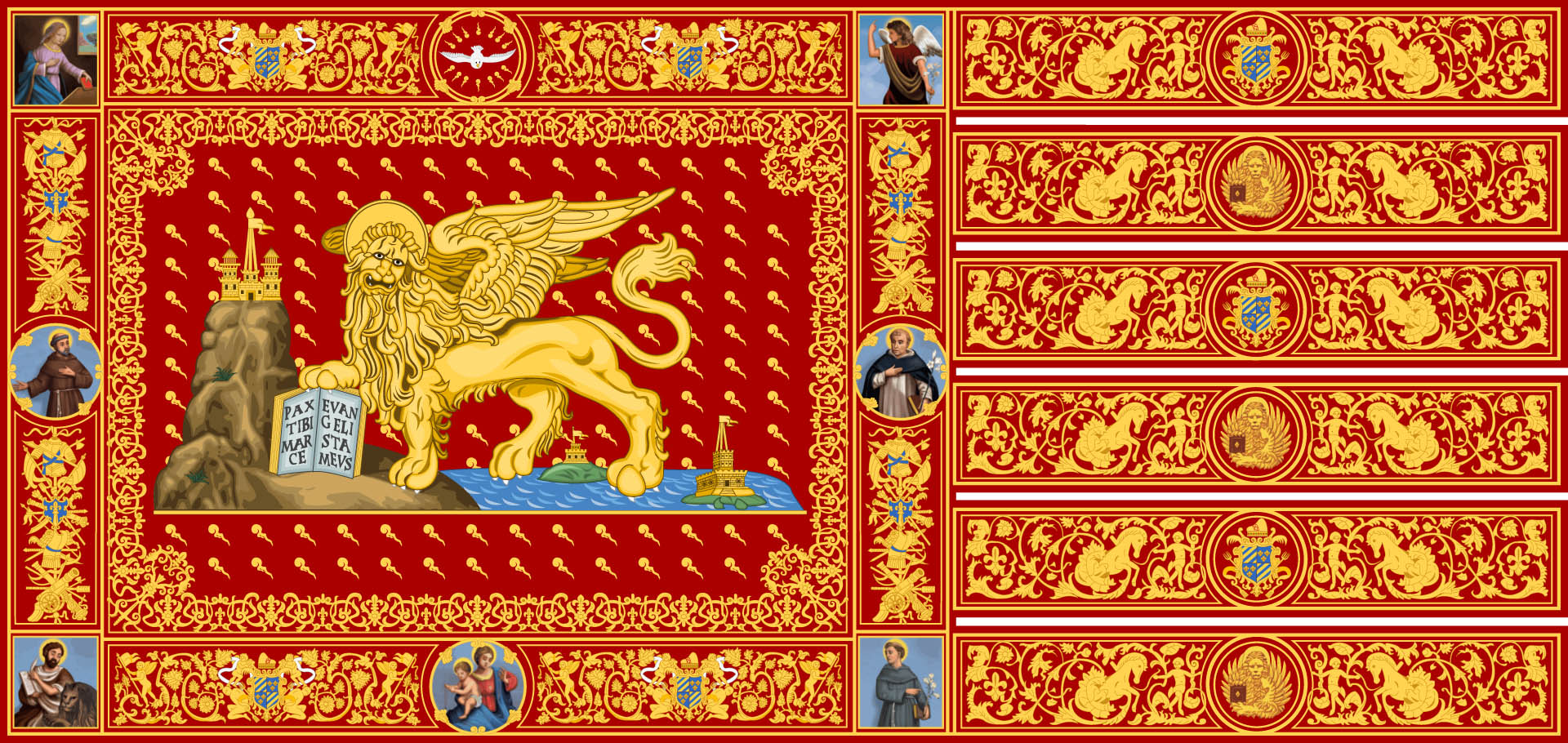

After the dominance of the Venetians in 1684 with the commander-in-chief Morosini, the situation seems to change. In his order on October 7, 1684, it is stated: “The prefects of the villages of the island of Lefkada, Fternou and Poros, complained to us that, although the island called Meganisi belongs to them, they are harassed from time to time by various Kefallinians and Ithacians, who independently claim to sow the crops in this land… ».

Finally, by decree of the Venetian Senate in 1691, the Commander-in-Chief of Iptanissos grants the land of Meganisi to Anastasios Metaxas from Kefallinia, along with the title of Count. The lands passed in 1716 to the locals and the staff of Metaxas, while in 1719 to Chiot refugees (around 130 people, Catholic in religion), always with the obligation to pay rent to the Venetian Administration. At the same time, settlers arrived from Akarnania, Ithaca, Kefalonia, and Lefkada itself. The scattered huts were connected and the first two small settlements emerged: “Kato Meri” and “Apanou Meri”, which corresponded to Katomeri and Spartochori. “Some Greek families from Xiromeros came to the islet of Meganisi and formed two small villages, consisting of about a hundred huts”, states the General Planner F. Grimani in his letter on 15.11.1760. The fact is also supported by the Municipality of Tselios-Ferentinos: “There were three soya residents. Thiacians, Xeromerites and Kefallinians”.

The next few decades seem to flow calmly and poorly on an island struggling to stand on its feet in an uncertain and insecure environment. Ragavis mentions that at this time the island is surrounded by Neapolitan coral fishermen, since its coasts are “great fields of beautiful coral”. This allows us to assume that the local element must also gradually turn towards the sea again, as its tradition extended.

Of course, Meganisi does not have the population, nor the means to man a combat-worthy fleet, however, in the Orlofikas of 1768 we find two Meganisiites among the 43 denounced mutineers.

The arrival of Revolutionary France in the Ionian Islands in 1797 initially causes excitement, but the economic measures are unsustainable and the Napoleonic rule is short-lived. Thus in 1798 the Russian-Turkish fleet gradually occupied the Ionian islands and in 1800 the independent state of Iptanissos was established, since it was a tax tributary to the Sultan. Meganisi then appears to have some form of self-administrative representation, in the form of provosts. Its two settlements are called “Diministres” (from the wheat that ripens in two months) in Katomeri and “Vagenospilia” in Spartochori. whose famous names are Kolokotronis, Karaiskakis, Androutsos and Lepeniotis. “With all the two hundred men of Lepeniotis, I took the boats and we sailed to Meganisi, and chased the French, and we stopped there”, says Kolokotronis about the year 1810.

The revolutionary and nationalist flame that flares up all over Europe does not leave this corner of the Ionian Sea unaffected. Small-scale uprisings, for more rights and less taxation, also find Meganisi participants. English occupation since 1815 is however ironclad and mutineers are punished exemplary and hideously. Under the shadow of the gallows, many escape to Xiromero to take part in the armed struggle that is coming of age. And this is because the population of the island belongs to the “people” and not to the privileged “arons”.

Rear Admiral W. H. Smyth reports: “Among the islets, Meganisi holds the primacy, as it is also introduced by the name. But since the stand of 1819 became a den of conspirators, I found myself under the necessity of disarming the inhabitants by settling in it, and for a time to limit intercommunication with the neighbours.’

And as for the general situation on the island, things are not rosier: “The first night we stayed in Meganisi and had the opportunity to see a significant part of this poor and barren island with a population of five hundred souls, concentrated in three villages, in rougher conditions than those living in the mountainous region of Djade, generally poor, impoverished and dirty. Men are said to be very lazy, while women are industrious and overworked. They depend for drinking water on two wells near the coast line…” an English traveler will write. Under these conditions, the participation in the Greek Revolution of 1821 is rather imperative for the people of Meganisi.

The most intense Meganisio presence in the Revolutionary period is embodied by the chieftain Dimos Tselios, later known as Gero-Dimos. His real name was Dimos Ferentinos, as he reveals in his fragmentary, saved from the fire, memoirs to Tercetis: “I was born in Meganisi of Agia Mavra. A Metaxas came and inhabited it. Our grandfathers, four Ferentine brothers, lived there.”

Gero-Dimos, born in 1785, lost both his parents in accidents at a young age and entered an Agiomavritiko home as a psychotic child. He returns to the island now a teenager and determined to board the commercial ships of the time. In fact, his brother owned one of them. Along the way, however, a swindler named Zafeiris wakes him up and drags him along to participate in the Race. This was in 1804. A year later he meets Katsantonis and a little later Karaiskakis: “We were following theft back then, various wars. They came and we grew. We continued. Antonis grew up, Turkey trembled. In 1805, Karaiskakis also came.” Dimos Tselios consistently continues his activity as a Thief and rises in the hierarchy while acquiring a close friendly relationship with Karaiskakis: “Karaiskakis from Premeti left prison. From place to place he came to Agrafa. He also became the first step, as I was too (…) Then with Karaiskakis I gained true love. Since then. We killed Liazaka Veligeka. We are forty, they are a thousand.”

Throughout the period up to the Revolution, he did not stay far from Meganisi. Although he is already married (he had six children), he usually visits the island with other chieftains: “In the winter we sit in a litroubio in Meganisi with Karaiskakis and Odysseus. Karaiskakis told me through the Company that it will happen in the spring. My family was in Meganisi. I went out. We went out.” Meganisi remains for Chelios the “inside”, the place of peace and respite from the grind of battle, the place that cares for his family. With the outbreak of the Revolution, not only his strategic acumen and his bravery, but also the boundless esteem that others had for him began to emerge.

“The Lefkadians under Dimon Chelion set out for Epirus and pursue the Turks, taking refuge in Valton and Xiromero”, says the historian K. Maheras and elsewhere it is written: “Lieutenant-general Demotzelios has shown his bravery and merit, and we do not doubt that we will always have reason to praise such a brave and such a modest warrior.”

From 1821 to 1829 the commander participated in twelve campaigns, twelve sieges and thirty-nine battles with the most important ones being those of Vonitsa, Mytikas and Lesinios, which he fortified, turning it into an impregnable fortress until liberation. He participated in both sieges of Messolonghi, from which he left due to illness, but without ceasing to fight outside. Perhaps the most important honor was given to him verbally after the battle of Arachova, from the mouth of Karaiskakis himself: “The activity of general Dimos Tzelios was also exemplary, who captured the most important one alive, killed about 15 by himself, and since the killing of the enemies is numerous, I don’t know, maybe he killed more. I only tell you this that in every season he shows great bravery”.

After the liberation and the arrival of Othon, in 1836 we find the Municipality of Tselios leading a movement with demands for the expulsion of the Bavarians who were infesting public life and the drawing up of a Constitution. The movement fails and he self-exiles himself in his homeland, financially impoverished and morally depressed. Tercetis reports on this: “The day before yesterday I saw in the street of Athens in scanty dresses, much more scanty, immersed in sorrow, the look of his face was similar. I saw the commander-in-chief Democelius (…) neither letters of pilgrims, which I read, nor fear and gifts of the enemy persuaded him to betray the flag, which he even saved as a shroud of death. Suffering Greece. Your true children are nourished by their tears, they are babbling or babbling in the streets.”

Tselios dies in 1854 in Agrinio. The ranks that had been taken from him were returned to him in 1843, while his bones were transferred to Messolonghi in 1901 and later to the Garden of Heroes. His effigy was set up in Meganisi, gazing at the places he liberated only in 2006.

Until the union of Eptanis with the rest of Greece in 1864 in Meganisi, the patriarchal feudal system prevails, where some aristocratic families own most of the land as well as the means of production (windmills, oil mills, boats, etc.), such as the family of Aristotelis Valaoritis . Hers was one of the six windmills that dominates Katomeri today and is called “Paliomylos”, as well as many estates that, as was customary, were sublet. The poet himself often came to the island and even had Meganisi people in his employ. It is reported that the first phrase of the eulogy for Patriarch Gregory Eʹ comes from the lips of a fisherman from Meganisi.

In Meganisi there has been a Municipality since 1829 and it was officially recognized after the Union with a royal decree of 1866. It has two villages (Vathi, Spartochori) and includes the islands of Skorpios, Madouri, Cheloni, Kythro, Thilia, Agios Nikolaos, Sparti and Petala. The Municipality is abolished in 1912 and we return to two communities: “Vatheos” (Vathy and Katomeri) and “Spartochoriou”.

The economy is based on the domestic production of oil, flax, wine, barley, wheat, while fishing and trade are gradually increasing. The trade in stone used for the construction of the Lefkada mansions is also mentioned in particular.

Religion continues to play an important role in the lives of the inhabitants, since at the beginning of the century a smallpox epidemic led the faithful to transfer the sacred Chariot of Agios Bessarionos (1489-1541) from the Trikala Gate for prayers to Meganisi. Since then he is considered the patron saint of the island and in 1910 the homonymous church was built.

Cultural activity is also present, since from 1880 “Erotokritos” by Kornaros was performed in Katomeri and later other folk theater performances such as “Golfo” and “Sclava” by Peresiadis.

This in itself leads us to the conclusion that the standard of living is significantly improved compared to the rest of Lefkada, which is also indicated by the population of the island: In 1920, there were 1644 inhabitants. In 1928 the population increased to 1650, while in 1940, to 2054, at a time when other villages of Lefkada barely exceeded three hundred souls. In addition, Meganisi has the highest percentage of high school graduates, even higher than the capital Lefkada.

The stagnation of the population during the interwar period has to do with immigration, a phenomenon that will intensify after the war. It is estimated that during the first decade of the 20th century alone, 210 people (mainly men) emigrated from Meganisi to America or the South. Africa, i.e. 1/8 of the population.

In the historical turning point marked by World War II, the island did not remain unscathed. In the initial recruitment, about forty Meganisians start as if in a festival for the Albanian front. Finally, no participation in the hostilities is mentioned. However, Meganisi does not remain unmoved and despite the monetary crisis and the demand of its boats, it sends clothing to the belligerents. The name of the “Papa” cave is often confused with that of the “Papanikolis” submarine. The truth is that the natural cave got its name not because it was a base or hiding place of the famous submarine, but because it was a hiding place for medieval believers and their priest from pirate raids. However, the action of other submarines in the territorial waters of Meganisi has been reported as well as the torpedoing of an Italian probe in 1942.

In Easter 1941, a group of high-ranking military personnel of the Serbian Staff, led by Marshal Simovic, fled to Meganisi. It is assumed that among them was the later marshal “Tito”, who at the same time escaped through the Ionian Sea to the Middle East.

The arrival of the Italian fascists in the same year changes the lives of the residents. The Italian force numbers only twenty people, but they apply shady methods such as curfews and blackouts, and they do not hesitate to drag into prisons or beat up dissidents. At this time there are also phenomena of blackness, although in a small percentage. A rudimentary trade bridge with Central Greece is still maintained, either illegally, or with the tolerance of the bribed carabinieri and members of “Finance”.

In the same period (beginning of 1942) the Resistance begins to be organized using the well-known tripartite method. In essence, Meganisi is a resistance link between Lefkada and Xiromero. In the archives of the EAM of May 1943, Meganisi is mentioned as “5th sector”.

In 1943, the EPON of Meganisi was also founded, which took on social (meetings) and cultural activities (staged “Foteinos”). In fact, it is the first time in a village of Lefkada that women take the stage, in 1944.

Often densely the island receives intimidating bombardments, and after the capitulation of Italy it is occupied by the Germans, four armed men and all.

The Resistance flares up and several Meganisians participate in armed action, such as the saboteur Varnakiotis, in Aetolia. Finally, the island pays its own blood tax to Eleftheria as two of the resistance fighters are arrested in Nikiana and taken to Agrinio where they are hanged on 27.7.1944. They were Dimitris Maroulis and Nikos Amarandos.

During the period of the civil war, we find exiled Meganisiites in the hell of Makronissos from 1947-50.

The Meganisio economy is trying to get back on its feet based on olive production, domestic animal husbandry and fishing. But it is gradually turning to shipping and immigration. Transportation is by boat and the transport to Piraeus by the famous “Glaros”. Rontogiannis characterizes the Meganisios as “shipowners” and “courageous ship owners”.. Meganisi then gives “some impression of affluence, in contrast to the deep impression of poverty caused by almost all the villages of the mountainous Lefkada”. Indeed, the existence of 22 merchant ships with a wide field of action is mentioned. At the same time, there is a shift towards education and scientific training, which will eventually bring out the new dynamic post-war generation, the other face of the island.

Nevertheless, the population begins a downward trajectory, which is explained once again by the new large immigration wave to Australia (mainly) and America. The devastating earthquake of Kefalonia in 1953 leaves Meganisi unaffected, like other large earthquakes afterwards, probably because of its geological (limestone) infrastructure. In the sixties, a new kind of side trade flourished, that of contraband cigarettes, which brought risks but also fat incomes to those involved.

During the period of the Hounta, we find in the cages of Gyaros and Meganisiotis a representative, Lambros Dagla.

With the Postcolonization, the face of the island essentially begins to change, mainly technologically, although the population maintains its elliptical tendencies, due to the internal migration this time to Patras and Athens.

Thus, in November 1974, Meganisi was electrified for the first time and acquired a telephone connection two years later. However, water supply still remains difficult and is done from wells or even from water vessels, while almost every household has a private cistern.

In 1977 and until 1980 the island became the subject of an anthropological study, by the then Lecturer and current professor at the University of Melbourne, Roger Just. His book “A Greek Island Cosmos” is a vivid depiction of the Meganisio society before the advent of tourism.

In 1980, a high school was established for the first time in Meganissi and it is an important lever for the revitalization of intellectual and social life. In conjunction with the establishment of the Association of Apantachous Meganisiots “O Mentis” (already since 1976), which is active mainly in Athens, Meganisi seems to be breaking through the cocoon of its cultural introversion.

The decade of the 80s is therefore the bridge that bridges the post-war Meganisi with that of modernity. Oil production gradually declines and the economic scepter falls to the shipping exchange. Tourism from being opportunistic acquires a certain organization. In 1984, the first Meganisio ferry boat was put into operation, and three more were subsequently built, modernizing transport. In 1985, the water of Vakeri reached the island, solving the permanent problem of water shortage.

At the end of this productive decade, the communities join a voluntary merger and after eighty years, they again form the Municipality of Meganisi (1990).

In 1993, Meganisi knew the honor of representation for the first time in the National Parliament, in the person of Panos Palmos.

Since 2002, Lyceum classes have been added to those of the Gymnasium.

The gradual obsolescence of shipping turns the economic activity towards the tourist product with all the positive and negative effects this entails.

The construction activity is gigantic and non-Meganisians become owners of large areas of land, while hotels and tourist accommodation are constantly being erected.

In the 2001 census, the permanent residents of the island amount to 1092 and in 2011 1042 are recorded.

What weight does the new multilingual identity of the island have in relation to its natural beauty? What kind of coexistence is that of children playing carelessly in the street and countless cars? Of the trendy shops and the grandmothers with the traditional costume intact, like a second skin? Of reinforced concrete and freshly whitewashed courtyards with pots of basil? Is Meganisi today the place of contrasts? Is he still, after so many centuries, searching for his identity and his footsteps or is he bawling in the cradle of his lost innocence? Will it forever be “a verdant coral cast on the Ionian apron”? Time will tell…

“Who are you and where are you from? Where are the place and your parents?’ For the well-travelled people of Meganisi, the eternally in love with their island, the words of Geros Dimos answer this question: “It was our home in Meganisi, a beautiful island, as if in Paradise”.

Bibliography

- Omiro, Odyssey, INSTITUTE OF NEW GREEK STUDIES, Thessaloniki, 2006, mtf. D.N. Maronitis.

Kostas Palmos, Meganisiotika, AGRAMBELI, ATHENS 1992. - Benton Sylvia.1934. “The Ionian Islands”, Annual of the British School at Athens 32(1931-2):213-46.

- Leekley Dorothy and Robert Noyes. 1975. Archeological Excavations in the Greek Islands, Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Press.

- Stravon, Geographical, 8, 332, ed. KAKTOS, ATHENS 1992, mtf. P. Theodoridis.

- Pindar, Nemean-Isthmonian, ed. KAKTOS, ATHENS 1992.

- Herodotus: 5. Terpsichori, ed. KAKTOS, ATHENS 1992, mtf. Cactus Philology Group.

- Virgil, Aeneid VII 735 (“Teleboum Capreas cum regna teneret”), www.thelatinlibrary.com/verg.htm.

- Yearbook of the Lefkada Studies Society, vol. Βʹ.

Rontogiannis, History of the Island of Lefkada, ed. SOCIETY OF LEFKADA STUDIES, ATHENS 1980. - Euripides, Iphigenia in Avlidis, ed. KAKTOS, ATHENS 1992, mtf. Κ. Georgousopoulos.

- Dimitris Tseres, Lefkada Through History, http://lefkada.gr/pages.asp?pageid=630&langid=1.

- Philostratus, Ta es ton Tyaneus Apollonius, Eʹ: XVIII, ed. KAKTOS, ATHENS 1992.

- Plinii Secundi, Naturalis Historiae Libri, XXXVII, (www.google.books.gr).

- Christopher Bondelmondi, Librum Insularum Archipelagi, Lipsiae et Beroloni, 1824.

- Testimony of Dimitrios Politis, archaeologist.

- Κ. Machira, Lefkas during Venetian rule, 1684-1797, ATHENS 1951.

- Georgios Tertsetis, Autograph Memoirs of the Municipality of Tseli, Tertseti Apanda, vol. Bʹ , ed. CHRISTOS GIAVANIS, ATHENS 1967.

- Smyth, Rear- Admiral W.H., The Mediterranean: a Memoir, Physical, Historical and Nautical, John W. Parker and Son, LONDON 1854.

- Davy, Notes and Observations on the Ionian Islands and Malta e.t.c., Vol 1, Smith Elder &Co, LONDON 1842.

- Κ. Machira, Lefkas 1700-1864, ATHENS 1956.

- Greek Chronicles Magazine, vol. Bʹ , II, 7.2.1925.

- Kostas Palmos, DIMOTSELIOS, PIRAEUS 1997.

- Roger Just, A Greek Island Cosmos, SAR PRESS, James Currey, OXFORD 2000.

- Spyros Vrettos, The folk poets of Lefkada (1900-1985) as a social phenomenon, ed. Kastaniotis, ATHENS 1990.

- Eyewitness testimony, Lambros Daglas.

- Testimony Fr. Gerasimos Konidaris.

- Costa Palmou, The Serbs in Meganisi, ep. Meganisiotiki Antilali, approx. Bʹ – 8, April 1999.

- Zois T. Koutsautis, THE NATIONAL RESISTANCE IN LEFKADA (Italian and German occupation), published by P.E.A.E.A. LEFKADAS, ATHENS 1991.